Health Technology Showcase

Five Questions and an Elevator Pitch: Anxieteam

1. What is the need that your project seeks to address?

Zane: We looked into the interactions between anxiety and epilepsy to see where anxiety might present as epilepsy or vice versa. We found that there's a really strong body of literature relating the two.

Blake: In a number of cases, someone experiencing treatment-resistant anxiety may be having a subclinical seizure or a non-motor seizure that's localized in a deeper structure of the brain. They're outwardly presenting with anxiety symptoms, but internally, they’re having an epileptic seizure.

We wanted to find a way to better identify when these subclinical seizures are occurring so that we could provide treatment to people who often go years without knowing their true underlying condition. If a person has focal temporal lobe epilepsy, it may respond to anti-seizure drugs, but it won't respond to SSRIs [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors] or other anti-anxiety medications alone.

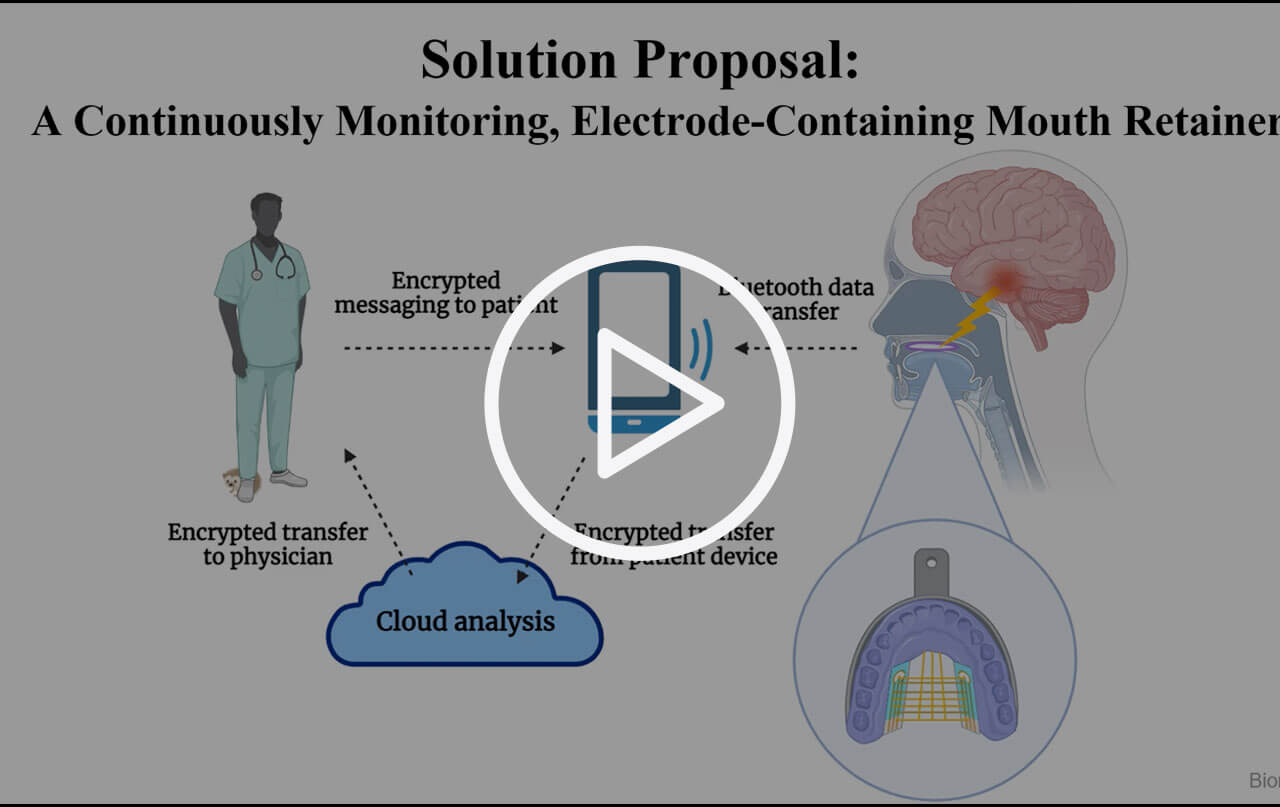

2. How does your solution work?

Blake: We created an intraoral electronic device that measures electrical activity through the roof of the mouth. Right now, the main diagnostic tool to determine if a patient is having an epileptic seizure is an EEG [electroencephalogram], which uses electrodes placed on the scalp to measure electrical activity of the brain. The device doesn't provide a direct measurement of brain activity, but it does correlate electrical activity through the skull. The challenge is that, because of interference from the brain’s structures, you can't always detect irregular electrical activity past a certain depth.

You can indirectly measure electrical activity using some deep neural models, which may provide up to 40% accuracy, but that's not great. We needed a better option. Our thought was that if we could measure electrical activity by going in the opposite direction, we might be able to record EEGs. They might propagate through the palate.

Zane: Because of the way EEG works, the standard of care for diagnosing epilepsy requires a patient to typically stay in a hospital wearing a full EEG cap until they are recorded having a seizure. It’s expensive and inconvenient because they often have to stay there for weeks.

We found a number of techniques that tried to record EEGs in a similar manner, but they were all either somewhat or fully invasive. We thought that the best candidate to measure electrical activity non-invasively would be from the roof of the mouth. Our device takes the form of a retainer. It's very easy to use. One of our major goals is to allow the user to wear this device without it restricting their activities or daily routine. It also enables ongoing ambulatory EEG monitoring.

Zane Norville (left) and Blake Salvador (right)

Zane Norville (left) and Blake Salvador (right)

3. What motivated you to take on the project? And what activities have you undertaken?

Zane: My motivation was seeing the huge unmet need in this area and trying to find some way that we could chip away at it. The average time a patient with non-motor mesial temporal epilepsy goes without receiving an epilepsy diagnosis is on the order of about 10 years. During that time, their seizures are untreated and often get progressively worse.

Blake: I have friends and family that have struggled with anxiety and other health issues. It's very frustrating for them. And I've been in the position personally where my doctor was trying to determine whether I had experienced a panic attack or a seizure and never found an answer. I thought the difference between the two would be clear. While hasn’t been a huge problem for me, it's still a problem. The diagnostics should be better. An accurate epilepsy diagnosis shouldn't take 10 years.

Zane: To advance the project beyond class, we considered designing and building a human model that would use ballistics gel to represent the brain and certain composite plastics to represent the roof of the mouth, creating a one-to-one size model of a human head. We would insert signal generators into that brain around the temporal lobe and deep brain structures, which would send a pulse at the amplitude of a normal seizure to create the simulation.

We tried a number of things but it turned out that it was a lot easier, and perhaps even more representative, to use a pig’s head. We acquired a pig from the butcher at the slaughterhouse.

Blake: I drove up to Petaluma to get the pig’s head. We used one with and without a brain and compared the accuracy of our data. For the most recent model, we used the pig’s head without the brain. We poured a solution into the brain cavity, letting it dry and solidify. Then, we inserted a signal generator into the ‘brain’ and an electrode into the soft pallet of the pig, which was roughly the same distance from the brain as in the human model.

4. What’s the most important thing you learned in advancing your project?

Zane: Knowing when to pivot. It’s important to be able to say, ‘Maybe this doesn't work. We're going to retool it a bit.’ We've had to do that when we’ve run into issues with hardware, or when our approach or a piece of data wasn’t useful in determining what we needed. All the way up to addressing our overarching needs, we kept asking whether we needed to rescope, change to a different patient population, or focus on a different set of outcomes. Overall, we all learned that this is a dynamic process, as opposed to being very fixed.

Blake: It’s also liberating and exciting to have a project that’s your own, and to know that you’ve become an expert. It's not like we're doing PhD work but, at the same time, not many people have ever done what we’re doing.

5. What advice do you have for other aspiring health technology innovators?

Zane: I'd emphasize the importance of understanding your need space, and really working on your need statement to identify a particular patient population, a defined set of outcomes, and a very specified set of quantitative metrics. That entire process is crucial in making sure that you're not wasting your time going down a bunch of rabbit holes. It allows you to focus your energy on a particular set of criteria that is going to yield the best results in the end.

Also, at the start, I definitely thought of myself as someone who worked in a wet lab. Be comfortable stepping outside of what you consider your area of expertise.

Original Team Members: Zane Norville, Blake Salvador

Course: Senior Bioengineering Capstone

NEXT Funding: Awarded for spring quarter 2022