Stories

Prescient Surgical: Building Acceptance for a Novel Technology

Coe, Koehler, and Suh when they initiated the year-long Biodesign Innovation Fellowship at Stanford University.

Coe, Koehler, and Suh when they initiated the year-long Biodesign Innovation Fellowship at Stanford University.

When they joined the Stanford Biodesign Innovation Fellowship in 2011-12 and were placed on a project team together, Jonathan Coe, Jeremy Koehler, and Insoo Suh discovered they had common interests and complementary skills. Coe had extensive surgical device development experience in engineering, marketing, and leadership roles, while Koehler’s medtech engineering experience focused broadly on product development, design, machining, manufacturing, and prototyping. Suh, an endocrine and general surgeon, was passionate about surgical innovation.

The three dove into the first phase of the biodesign innovation process, which involves observing healthcare delivery to identify important unmet needs. “We were all focused on advancing surgical practice,” recalled Suh. The critical problem of surgical site infections (SSI)—infections that develop after a procedure at the site of the surgery—captured their attention after observing a kidney transplant that resulted in an infection that the attending physician considered an inevitable outcome. “That experience brought the need into sharp focus. As surgeons, we have an innate sense for which of our patients have the highest risk of contracting an SSI,” Suh noted. “So why weren’t we able to proactively and reliably intervene to mitigate that possibility? That realization sparked our efforts to find a way to proactively address the root causes of infection during surgery.” [i]

Through research, the team learned that while only 2-5 percent of total surgical patients acquire an SSI, in higher-risk abdominal surgeries, such as colorectal surgery, that rate can be as great as 26 percent. [ii, iii, iv] Costs to treat a patient with SSI are roughly twice as high as for patients without SSI, largely because patients with such infections typically spend an extra seven to 10 days in the hospital. [v, vi, vii] SSI is also the most common reason for patients to be readmitted to the hospital. [viii]

Moreover, at the time of the team’s investigation, SSI reduction recently had been identified as a national priority as part of an overall effort to reduce healthcare associated infections (HAIs)—infections acquired by patients in healthcare facilities. “Medicare rules require hospitals to report their rates of HAI, which includes SSI, to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Healthcare Safety Network,” said Coe. “Poor performing hospitals risk losing 1 percent of their Medicare revenue every year.”

“In light of these policy changes, we realized that developing a technology to prevent SSIs would not only help patients, it could potentially reduce healthcare costs,” Coe continued. The team grew more excited when their research revealed that, while surgeons have diligently focused on surgical techniques to reduce infection risk, “The data highlighted continued intraoperative vulnerabilities at the surgical incision site, and the tools at their disposal were decades old,” he said. “So we really had an opportunity to define a new standard.”

With insight from clinical mentor (and ultimately company co-founder) Dr. Mark Welton, then Chief of Colorectal Surgery at Stanford University, the team decided to pursue an innovation project in this area. “I was always bothered by the assumption that infection was an inevitable outcome for some patients undergoing higher risk surgeries,” said Welton. “Surgeons needed better tools and technologies to address the root cause of these infections.”

Developing a Solution

After establishing a deep understanding of the pathophysiology of surgical site infection, the team studied existing surgical practices and current methods of infection control. Suh explained the limitations of the most common approaches: “Incomplete skin antisepsis introduces bacteria into the incision, and passive wound protectors cannot clear the invading bacteria. Manual irrigation is disruptive and can spread bacteria. And prophylactic antibiotic concentrations at the incision can fall below inhibitory levels.”

Given that SSI is a local phenomenon, the team believed that targeting the delivery of the therapy at the surgical site was critical. “In contrast to systemic therapies that are circulated throughout the body to achieve a preventative effect at the surgical site, we wanted to design an approach that would concentrate the therapy where the threat of bacterial contamination is the most critical,” Koehler said.

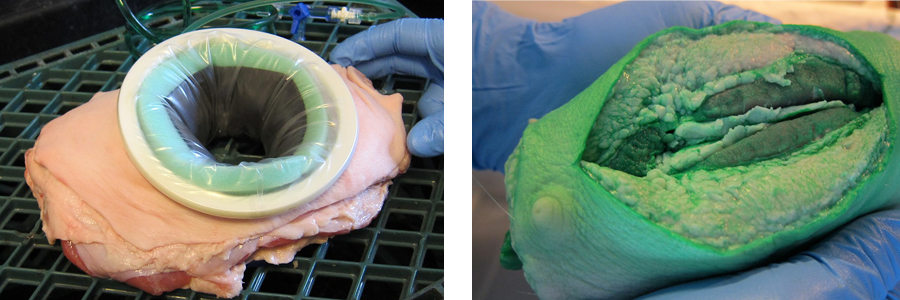

Inspired to devise a better approach, the team honed in on a lead concept for reducing SSIs: delivering therapeutic fluids directly and consistently to the surgical site to protect it. “We wanted to develop a device that a surgeon could use during the procedure that would diffuse a therapeutic fluid directly into the tissue to actively cleanse the incision site,” Koehler described. An early experiment in the wet lab helped demonstrate their basic idea. “We were able to diffuse a bright green fluid through a plastic membrane, and it was very easy to see that the fluid penetrated the tissue locally,” he recalled.

The ex-vivo tissue model (left) and results (right).

The ex-vivo tissue model (left) and results (right).

By the end of the fellowship year, the team had core concept for their solution, but they did not have a working prototype. “I remember, we all went to a local café to decide whether to try to take our idea forward,” said Suh. “We didn’t have a device, we didn’t have data, and we needed funding and a place to work.” But the team voted unanimously to press forward, naming the company Prescient Surgical. After applying for several grants, they raised just enough funding to keep working over the summer and into the fall of 2012.

Although their concept was intuitive, developing a design that would hold the wound open and deliver fluid to the tissue proved challenging. For weeks, Koehler and Coe worked nights in the Stanford Biodesign prototyping lab, running through more than a dozen wildly divergent prototypes including an inflatable model, one with pull cords, and another that used a spiral mechanism. “At that point, Jon and I were building all kinds of stuff, cranking through a prototype a week, just racking our brains and testing the limits of the fabrication techniques at our disposal,” said Koehler.

Two early models with which the team experimented.

Two early models with which the team experimented.

Eventually, Koehler had a breakthrough. “I had been exploring various linkage designs but Jon and I were concerned about the manufacturing costs and overall complexity of these models” he remembered. However, he gleaned some important insights when he stumbled upon a discontinued toy, the Hoberman Flying Disc. “It’s a simple expanding flying disc, like a Frisbee, but I discovered a few design tricks from it that could make the linkage approach feasible.” Koehler built a prototype inspired by, and in part made from, that disc. It had an expanding ring to accommodate different incision sizes, a membrane that delivered fluid, and suction at the bottom to prevent pooling and help remove incisional contamination. The prototype resembles Prescient’s final product today.

The model inspired by the Hoberman Flying Disc.

The model inspired by the Hoberman Flying Disc.

Winning Over Surgeons

They shared the new prototype with Suh who, according to Koehler and Coe, “hardly ever liked anything.” He said nothing but smiled broadly, indicating that they had finally come up with something that could potentially to appeal to surgeons.

As prototyping progressed with this new direction, Coe met with surgeons to seek their input. Through these interactions, he uncovered a challenging dynamic. “SSI is a sensitive issue. Surgeons are interested in improving infection rates generally, but there are profoundly different schools of thought on how to do it,” he said. “Some simply attributed SSI to poorly trained staff and unclear protocols and procedures. Others were willing to accept a certain level of SSI with higher risk surgeries. But when we talked to infection control experts like Dr. Donald Fry and Dr. Motaz Qadan, they recognized the potential value of new technology to fight SSI and how it could fit into hospital infection control programs.”

By working with their advisors to better understand the surgeon mindset and seeking additional input from the infection control specialists, the team concluded that cultivating a community of early supporters would be key to their continued progress. They also would have to design their commercial device to fit seamlessly into existing surgical and infection control workflows in order to increase its chances of being adopted.

With these goals in mind, they refined the disc model and then assembled a group of carefully selected surgeons to join them at the Stanford cadaver lab to test variations of the device in human anatomy. This experience yielded important insights that helped them continue to improve their design. It also generated a positive response from the surgeons in attendance, adding to their cadre of early supporters.

Advancing to Market

By May 2013, the Prescient team had a working prototype and enough early data to raise seed funding and secure a home at The Fogarty Institute for Innovation, a Silicon Valley incubator for promising medtech start-ups. With the help of Dr. Welton, they connected with forward-thinking clinical partners in colorectal surgery, including Dr. Harry Papaconstantinou, chairman, department of surgery and gastrointestinal surgeon at Baylor Scott & White Health. “We learned one big lesson in our discussions with surgeons,” said Coe. “To be very clear and real about our desire to provide them with tools and technologies to enhance their existing infection control programs. Hospitals need partners in fighting infection, not just vendors.”

At the same time, they turned their attention to getting regulatory clearance and preparing for first-in-human use. “We were moving fast at that point, bolstered by the support we received at the Fogarty Institute,” Coe said. “Going from concept to a validated, sterilized device took us less than six months.”

In January 2014, they reached their first-in-human milestone and submitted their regulatory application on the “CleanCision” device. “We believed that our technology, which was considered to be non-significant risk by physicians and hospital review boards alike, was ideal for the 510(k) clearance pathway. Our plan was to get approval quickly and get into the market on a limited basis so that we could continue to learn, iterate, and build support for the system,” Coe explained.

However, they soon learned that the FDA would require them to follow the de novo pathway based on the novelty of the device. “In many ways, it was encouraging that the FDA saw the technology as being really new and different,” Coe said. “But this decision created a need for substantial additional data to support the creation of an entirely new product classification.” It also caused considerable uncertainty and increased risk for the team since it was impossible to predict the duration and requirements of the de novo process.

“After spending months communicating to our investors that 510(k) clearance was forthcoming, I had to drop the bombshell that we would have to gain de novo clearance first. And because of that, we had to raise more money,” Coe remembered. “Fortunately, we had a group of investors who really believed in the need we were addressing and were committed to our longer-term vision.”

To support the new regulatory submission, the Prescient team needed to generate evidence to demonstrate that the active clearance mechanism employed by CleanCision was safe and effective in addressing the root cause of SSI. “The principal behind the device is that it significantly and continuously decreases the amount of bacterial contamination at the incision site,” said Suh. “So we launched a multi-center clinical study in colorectal surgery in which we evaluated cultures of exposed wound surfaces and surfaces protected by our device. Our early scientific advisors, some of the most respected in the field of infection control, were instrumental in helping us design and implement the study.”

The results showed that the level of bacterial contamination on the protected surfaces was roughly 70 percent less than on the exposed surfaces. “This translates to a wound infection rate that, compared to historical data, was dramatically reduced,” he continued. “On average, for the type of surgery in the study, infections at the wound occurred in 10-15 percent of cases. Our rate was 1-2 percent. It was remarkable.”

The strength of their safety and effectiveness data eventually led to the FDA’s decision to clear the CleanCision Wound Retraction and Protection system through the de novo pathway in December 2016, nearly three years after the company’s initial 510(k) submission. Critically, the clinical data generated during the FDA review attracted many early adopters to the technology. Additionally, through its multiple trials, the company gleaned important insights to make the CleanCision system more effective and robust. Accordingly, the Prescient team decided to seek clearance for its second generation system before releasing it to the market.

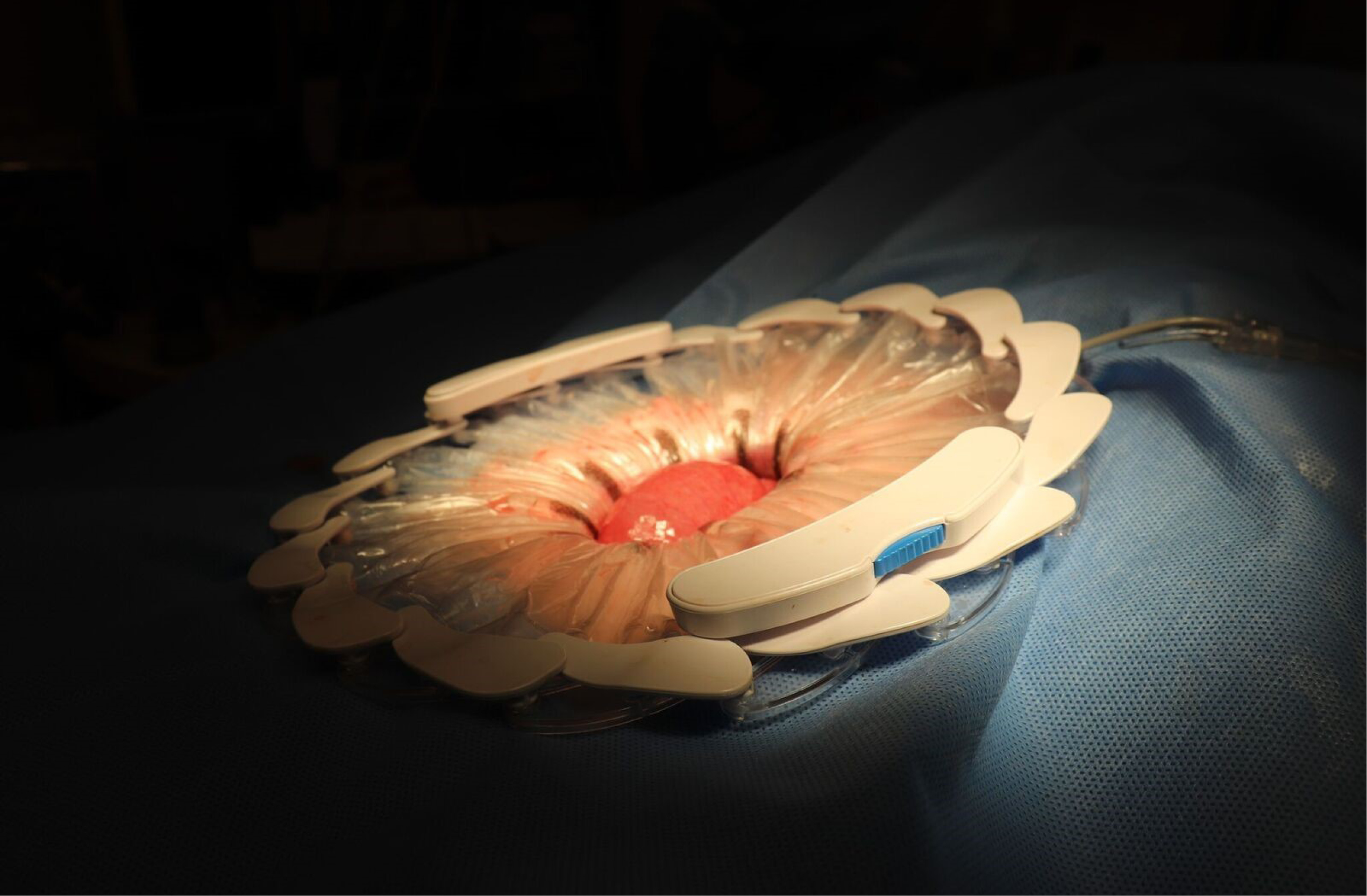

The CleanCision system.

The CleanCision system.

In December of 2017, Prescient received FDA 510(k) clearance and was ready make the new CleanCision system commercially available in the US. Reflecting on the company’s journey, Coe noted, “You can’t anticipate every challenge along the development path. Innovative approaches in translational medicine challenge ingrained habits and inherent biases. But, by the same token, innovators bring their own biases to the table. The key is to listen carefully to your potential users, iterate, and commit to a long-term partnership to solve their unmet needs. We came to fully appreciate that surgeons and their teams are leaders, problem solvers, and healers. And we made it our mission to collaborate with them in the quest to eliminate surgical infections.”

[i] All quotations are from interviews conducted by the authors unless otherwise cited.

[ii] Anderson DJ, et al., “Strategies to Prevent Surgical Site Infections in Acute Care Hospitals,” Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, October 29, 2008, pp. S51-S61.

[iii] Wick EC, Shore AD, Hirose K, Ibrahim AM, Gearhart SL, Efron J, Weiner JP, Makary MA, “Readmission Rates and Cost Following Colorectal Surgery,” Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, December 2011, pp., 1475-9.

[iv] Smith RL, Bohl JK, McElearney ST, et al., “Wound Infection After Elective Colorectal Resection,” Annals of Surgery, 2004, pp., 599–605.

[v] Broex ECJ, Van Asselt ADI, Bruggeman CA, Van Tiel FH, “Surgical Site Infections: How High Are the Costs?” Journal of Hospital Infection, July 2009, pp., 193-201.

[vi] Wick EC, Hirose K, Shore AD, Clark JM, Gearhart SL, Efron J, Makary MA, “Surgical Site Infections and Cost in Obese Patients Undergoing Colorectal Surgery,” Archives of Surgery, September 2011, pp., 1068-72.

[vii] Wick EC, Shore AD, Hirose K, Ibrahim AM, Gearhart SL, Efron J, Weiner JP, Makary MA, op. cit.

[viii] Morris M, Deirhoi R, Richman J, et al., “The Relationship Between Timing of Surgical Complications and Hospital Readmission,” JAMA Surgery, April 2014 April, pp. 348-354.