Technologies

InterVene Improving Treatment for Deep Vein Valve Failure:

An Interview with Fletcher Wilson of InterVene

What is the need InterVene seeks to address?

We’re developing a better way to treat patients suffering from chronic venous insufficiency due to deep vein reflux.

Deep vein reflux [DVR] is when the valves in the veins of the legs fail, causing blood to pool in the legs rather than traveling back to the heart. DVR can result in chronic venous insufficiency [CVI], a condition characterized by elevated pressures in the veins of the leg that can lead to swelling, pain, and open wounds or leg ulcers. Millions of Americans suffer from DVR and moderate to severe CVI, yet there’s little that can be done for them. The current standard of care is to combine compression therapy, leg elevation, and local wound care. But none of these treatments address the underlying problem of deep vein valve failure, so patient symptoms tend to become increasingly severe, debilitating, and costly to manage.

"The current standard of care is to combine compression therapy, leg elevation, and local wound care. But none of these treatments address the underlying problem of deep vein valve failure..."

What key insight was most important to guiding the design of your solution?

During our training at Stanford Biodesign, we learned about an existing surgical procedure called the Maleti Neovalve. The technique involves forming new vein valves out of the tissue of the vein wall itself. It had been shown to be effective, but wasn’t being widely used because the procedure was technically difficult to perform and highly invasive.

Intrigued, we started experimenting with veins on the bench at Stanford Biodesign and realized that we could potentially do the same thing using catheter-based techniques. We hodge-podged some devices together and created a valve that worked perfectly. This was the moment we realized we could replicate this surgical procedure without open surgery.

The InterVene team with the BlueLeaf technology.

The InterVene team with the BlueLeaf technology.

How does your solution work?

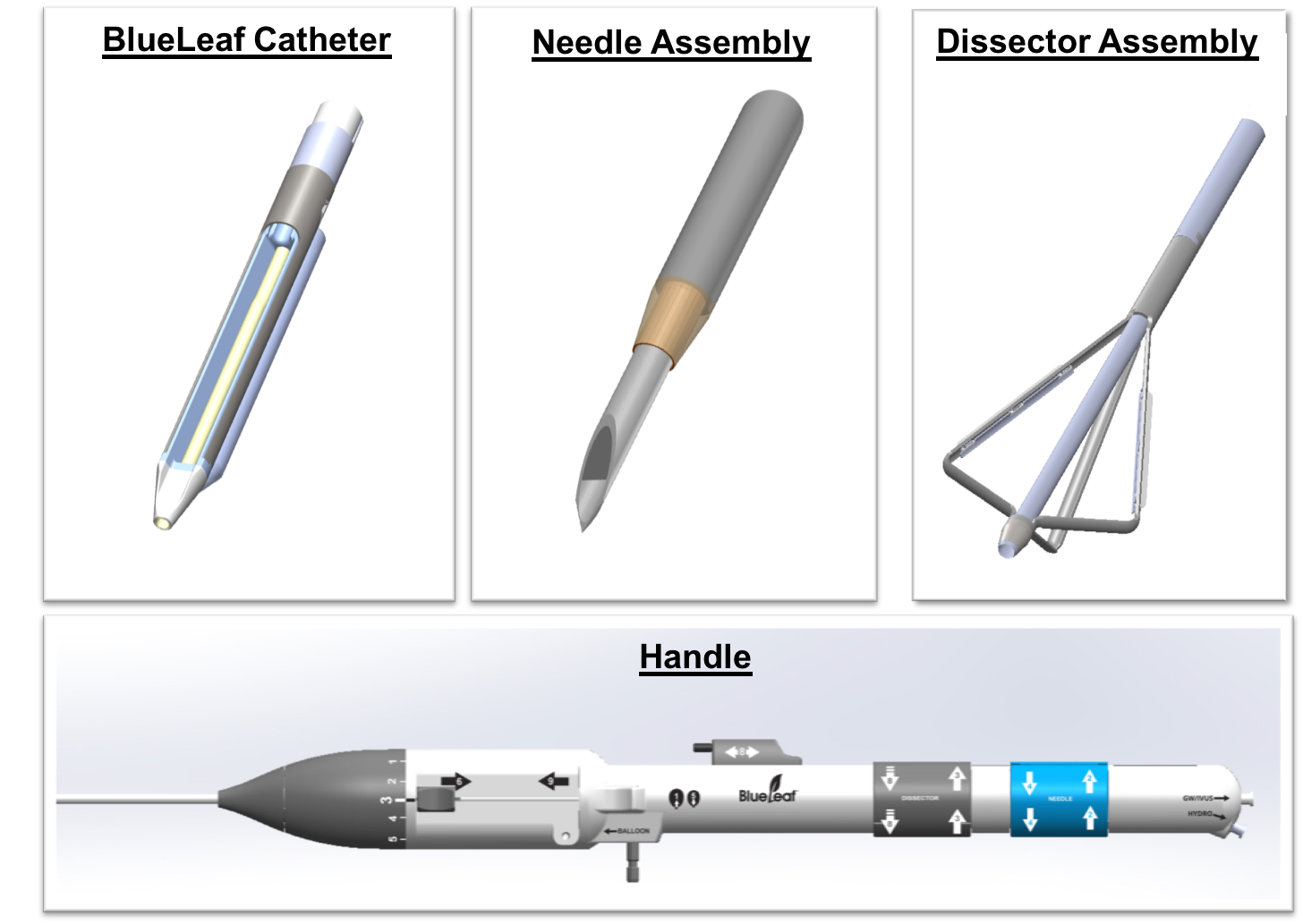

Our BlueLeaf system involves an endovascular device that’s intended to form new vein valves out of the layers of tissue that naturally make up a patient’s vein wall.

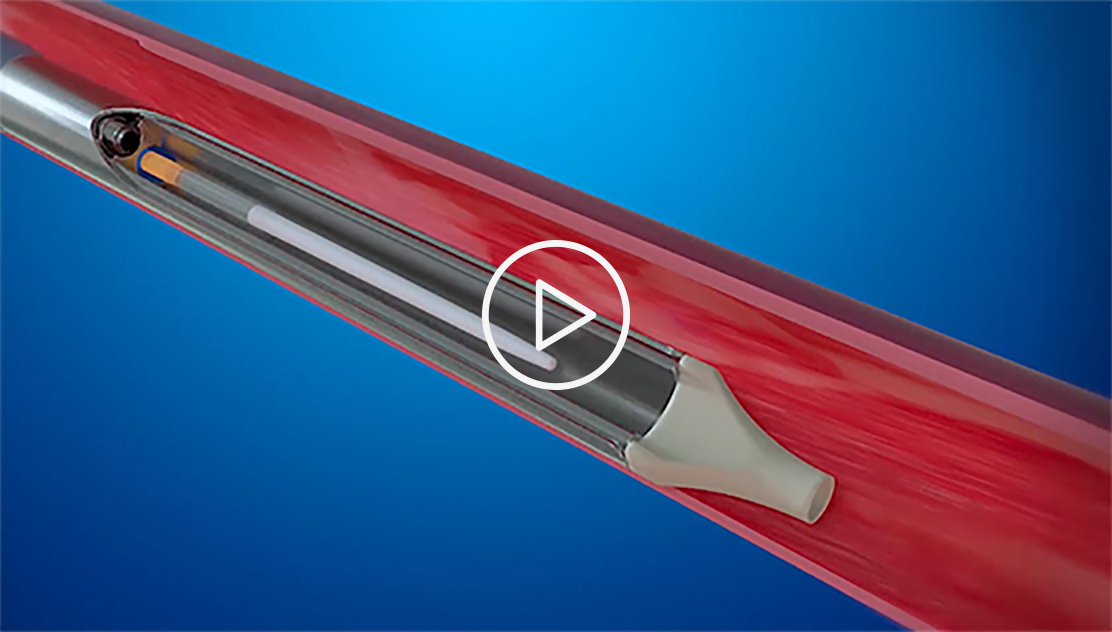

This short promotional video, provided by InterVene, illustrates how the company's system is intended to work (see endorsement disclaimer below).

This short promotional video, provided by InterVene, illustrates how the company's system is intended to work (see endorsement disclaimer below).

The vein wall is often less than one millimeter thick, so we use a novel form of hydrodissection to gain access. We insert a needle into the vein wall while ejecting a jet of fluid from the end of the needle. This creates a fluid-filled pocket between the layers of the vein wall, which gives us the space to insert a special tool and form a specific valve geometry. The new valve facilitates the flow of blood back up to the heart rather than allowing it to pool in the legs where it can cause devastating complications for patients.

As compared to open surgery, our percutaneous approach leverages the more broadly held interventional skills of multiple physician specialties and is much less invasive. The goal is to collect the clinical data required to allow a significantly larger pool of physicians the ability to offer a therapeutic solution to their patients suffering from DVR.

At what stage of development is the solution?

We’re currently conducting a pilot clinical study of the technology in New Zealand and Australia, and we recently submitted an application to the FDA to launch a US-based trial arm in the near future.

Tell us about a major obstacle you encountered and how you overcame it.

The development of this technology was more difficult than we initially expected. We needed a tool that forms a very specific valve geometry, but each patient’s tissue is different – with varying levels of disease and a range of sizes. Over 12 months, we explored more than 80 different iterations of the valve formation tool. In the end, we took two lead concepts forward in parallel and ultimately chose the one that created the best valves. But it took tremendous persistence from the engineering team to achieve this end result.

How did your Biodesign training help you advance the project?

It’s hard to raise money, especially for novel medical technologies requiring clinical trials to demonstrate their safety and effectiveness. I think the reason we've been able to attract investors is because the need is so compelling.

"Starting with an important need opens lots of doors and … should be a prerequisite for any project."

We’ve heard of potential investors calling a vascular surgeon or another expert in the field and, time and time again, they’ve been told, ‘That’s such a huge problem.’ Making sure a project is based on a meaningful patient need makes it more fundable and easier to get new potential employees and physician partners excited about it. There are many hurdles that need to be overcome, but starting with an important need opens lots of doors and, in my opinion, should be a prerequisite for any project.

Fletcher Wilson founded InterVene out of the Biodesign Innovation Fellowship in 2010. To learn more, visit the InterVene website.

Disclaimer of Endorsement: All references to specific products, companies, or services, including links to external sites, are for educational purposes only and do not constitute or imply an endorsement by the Byers Center for Biodesign or Stanford University.