Stories

Global Innovator Spotlight: Amit Sharma

Amit Sharma shared his story with high school student Sophia Nesamoney in the summer of 2017.

Amit Sharma shared his story with high school student Sophia Nesamoney in the summer of 2017.

Even as a boy, Amit Sharma was not afraid to question the status quo and tackle challenges from which others shied away. As a high schooler, he remembered wandering the streets, watching people go about their daily lives without seeming to notice the landfill amassing beneath their feet. He would ask his family why their neighbors ignored the reeking garbage and carelessly added their trash to the piles every day. Through these conversations, he learned that garbage was an uncomfortable topic in his community because many people felt powerless to address the problem. In contrast, young Amit saw an opportunity to apply technology and automation to solving this growing problem. He created an innovative garbage segregation system and then trained his neighbors to understand different types of trash and safely dispose of each kind.

The uniqueness and relevance of Amit’s waste management solution won him national prizes at science fairs across India and distinguished him from other students. These accolades piqued his interest in tackling other large problems that other innovators might be reticent to address. After completing a project to aid handicapped people, Amit became intrigued with issues related to health and healthcare. He was fascinated with how the complex components of the human body worked together and briefly considered becoming a surgeon. He was drawn to the idea of positively impacting patient lives through medicine but recognized that most physicians did this one patient at a time. As an engineer, he would potentially be able to help many more patients through the innovative application of technology to problems in healthcare. For this reason, when it was time to choose a career path towards the end of high school, he decided to pursue engineering.

Amit completed his bachelor’s degree and was then accepted into the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Delhi. There, he learned about the Stanford-India Biodesign program, which was founded specifically to train Indian innovators to identify important unmet medical needs in the country, invent new technologies to address the unique requirements of Indian patients and providers, and implement them locally. A professor encouraged him to apply to the program based on his interest in both medicine and technology innovation. Amit submitted an application, even though he was not confident that the Biodesign program would be the right fit for him. “At that point, I was skeptical,” he recalled. “I thought ‘What is this program going to teach me? I’m already doing these kinds of things on my own.’” However, looking back, he realized, “I was grossly mistaken. The program taught me so much more than I could ever learn on my own. It taught me to truly see possibility instead of impossibility in the world around me.”

As a member of the first class of Stanford-India Biodesign fellows, Amit devoted six months learning and practicing the biodesign innovation process at Stanford before returning to India to repeat it for Indian patients and doctors. Although he and his teammates spent hundreds of hours observing healthcare delivery in a variety of care settings, looking for the most important needs to address, their inspiration for the project they would ultimately take forward came from a more personal experience. At one point during their training, a team member who happened to be a physician, had to take a short leave to help look after his critically-ill while she was in intensive care. After this experience, the team jokingly asked if he had found any problems on which they should focus. To their surprise, he said, “I had access to all of the right resources and I knew everything about the type of care she needed to receive. The only problem I couldn’t solve was her fecal incontinence.”

From their clinical immersion, Amit and his team had already learned that fecal incontinence was a common problem in intensive care units because patients suffering from critical illness often have limited control over their bowels. The condition could become potentially life threatening when sedentary patients develop pressure ulcers that, in turn, become infected through contamination from the patient’s stool. In geographies outside of India, some technology solutions were available, but none had been widely adopted because of various limitations. In India, the standard of care for fecal incontinence was adult diapers and, even within the hospital setting, family members were often expected to play an active role in managing the incontinence of their loved ones. Wearing diapers was humiliating and embarrassing for the patient, and it offered little protection from infection for compromised skin tissue. Moreover, helping to change the diapers was awkward and unpleasant for the caretaker. A better solution was desperately needed for patients in care facilities, as well as those at home. Unfortunately, because the condition was distasteful and uncomfortable to talk about, medical technology companies seemed uninterested in tackling the problem, even though the related infections were extremely dangerous.

Amit knew instinctually that he and his teammates were the right people to solve this challenge. After years of additional research, product development, and testing, Amit, along with Nishith Chasmawala and Sandeep Singh, came up with the first device that uses a hygienic applicator to divert feces away from the body without allowing it to come in contact with the skin, thereby significantly reducing the patient’s risk of infection.

Over the years, India has become famous for Jugaad innovation, a frugal and improvisational approach to solving problems that has been widely praised as an alternative to traditional, mostly Western innovation methods. In Hindi, Jugaad means “to hack,” and the philosophy urges inventors to use resources that are easily and inexpensively available in their local communities to devise low-cost solutions that can be implemented quickly to realize near term improvements. When asked if his device is a good example of Jugaad innovation, Amit again is willing to take the stance of a contrarian. Although he sees the value of the Jugaad approach for certain types of problems, Amit does not think it’s right for every situation, and he worries that it may have unintended consequences, teaching Indians to settle for quick, inexpensive solutions instead of higher-quality approaches that are more scalable and sustainable in the long run.

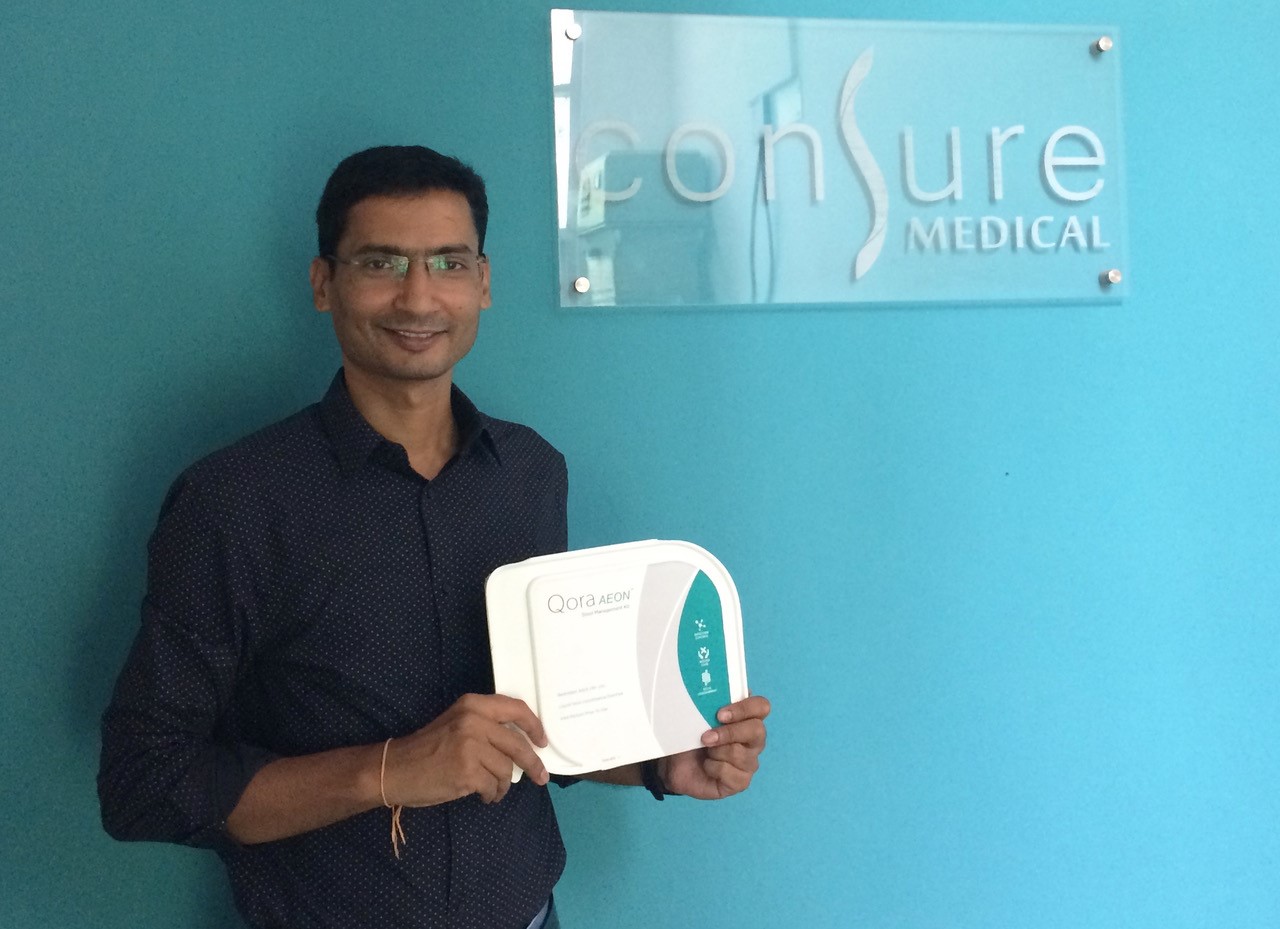

Amit and his partners went on to found Consure Medical to commercialize the team’s fecal incontinence solution. Their device is not a Band-Aid but rather an elegant, effective, solution that helps preserve the patient’s dignity. Unlike most Jugaad innovations, it has relevance beyond the local community where it was designed. After the team conducted rigorous scientific studies proving that the device provides excellent clinical outcomes, it was cleared by the FDA in 2014 and is now available in both India and United States. This has enabled Consure to serve a much larger audience than initially anticipated and made it possible for Amit’s company to scale and expand more quickly. With future versions of the product, Consure Medical has plans to bring down the cost of the technology to make it more affordable for all care facilities. They are also working to make the device simple enough to be used by a care provider or family member (rather than only nurses and physicians) so that it can help patients suffering from fecal incontinence at home.

Amit hopes that his story will inspire others to believe in themselves and reshape their parameters of what they think is achievable. He also wishes that instead of gravitating toward problems that seem safe and approachable, future innovators in India will challenge themselves to address more daunting issues. Finally, he hopes that more innovators will resist the “quick fix” allure of Jugaad innovation in favor of contextually appropriate, high quality, durable solutions to India’s health and healthcare needs. With this mindset, Amit believes that Indian innovators can play an important role in bringing more life-changing interventions to patients in India and beyond.

Sophia Nesamoney is a published author and a student at Castilleja High School in Palo Alto, California. She traveled to India in summer 2017 to interview Avijit Bansal and develop this story. She is also passionate about global health and plans to pursue a career in medicine and writing.