Health Technology Showcase

Five Questions and an Elevator Pitch:

PCR

In this short video, the PCR team explains the need they set out to address and how their solution works.

In this short video, the PCR team explains the need they set out to address and how their solution works.

1. What is the need your project seeks to address?

Chyna: Interstitial cystitis, or bladder pain syndrome, is a pain disorder primarily experienced by women. It affects between 3.3 and 7.9 million women in the US, and is characterized by severe pain in the bladder and lower urinary tract and frequent urination lasting more than six weeks. The intensity of the pain and constant need to void disrupt daily life. There is no cure and no single therapy that works for all patients. Instead, physicians typically try multiple lines of treatment until they find one that works. The problem is that many standard-of-care treatments are painful to deliver to the treatment site, and some, such as the oral medications, have potentially serious adverse side effects.

2. How does your solution work?

Peyton: One of the therapies recommended by the American Urological Association is a transvaginal injection of medication into the base of the bladder, which is called the bladder trigone. Because the bladder sits at the top of the vaginal canal, the needle needs to be positioned at a shallow upwards angle to go through the anterior vaginal wall and into the trigone. However, it is difficult to achieve the correct angle when delivering the injection.

Our solution is a needle delivery tool that guides the injection angle. It’s ergonomic, easy-to-use, and allows the practitioner to achieve the correct injection angle with minimal training. It’s cost-effective because it makes it possible for a less-skilled practitioner to administer the treatment. It also saves money by ensuring that the medication reaches the correct part of the patient’s anatomy. This is good for the patient in terms of pain relief and good for the health care system because some of the medications used, like Botox, are expensive.

3. What motivated you to keep working on the project and what activities did you undertake?

Remi: We made so much progress during the Capstone course that we were all really excited about the project’s potential to help patients. We had a working prototype that was ready to use at the end of winter quarter. We decided to submit our project to the National Institutes of Health DEBUT Challenge, a competition for undergraduate bioengineering students who have developed technology solutions to real problem in care. We also submitted an abstract to the BMES (Biomedical Engineering Society) competition. So, we used the extra time and funding in the spring to work with our clinical mentor, Amy Dobberfuhl, MD, to test our device in cadavers to see whether it could actually guide these injections successfully. This gave us proof-of-concept data to support our submission to the NIH.

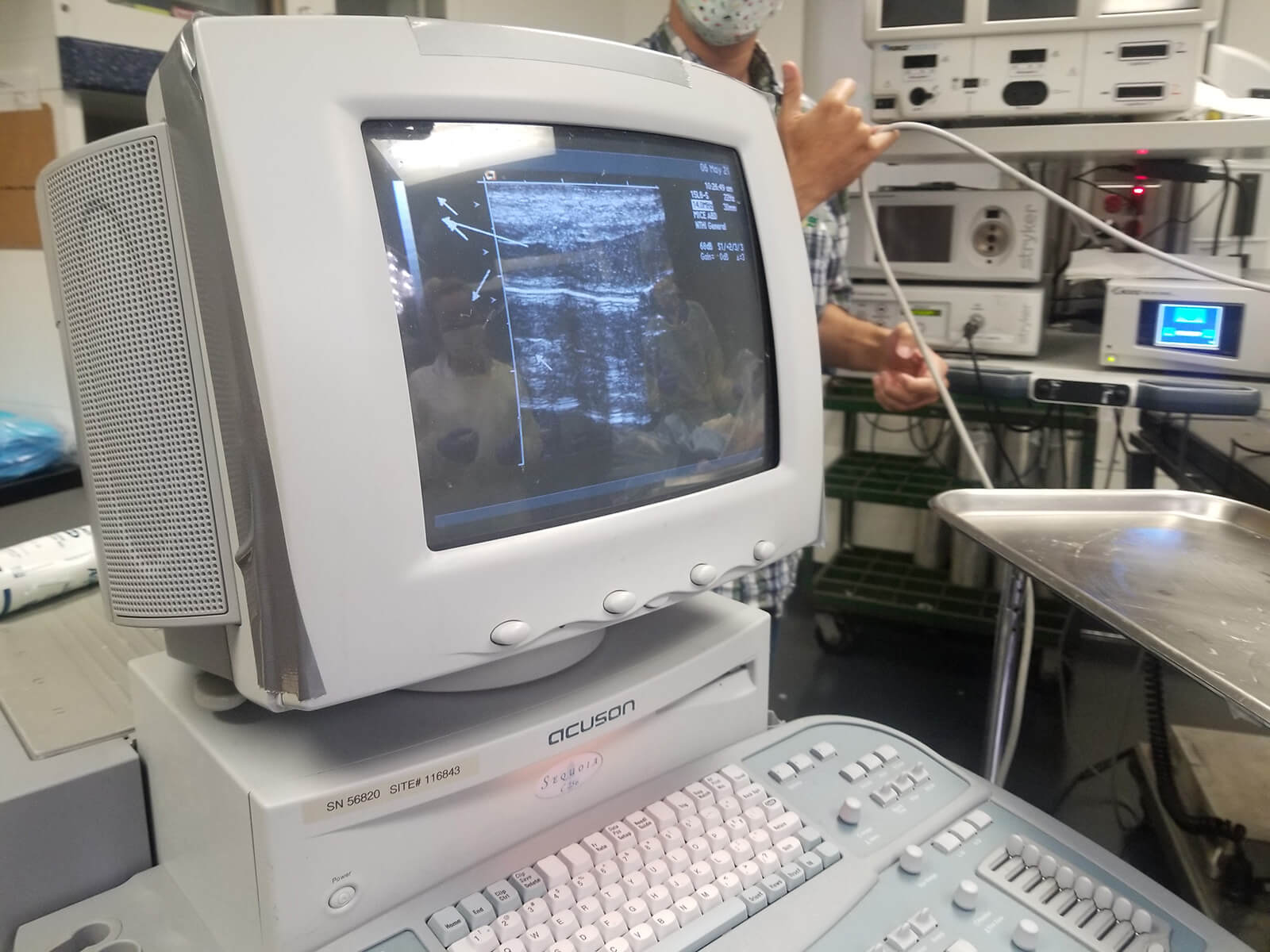

Ultrasound images showing positive results from cadaver testing

Ultrasound images showing positive results from cadaver testing

4. What’s one of the most important things you learned from advancing your project beyond the academic year?

Remi: The ability to test our device on cadavers gave us invaluable real-world feedback. It wasn’t always a win – there was one time when we couldn’t even use our device because of fit, but it helped us see that we needed to print our device in a number of different sizes in order to accommodate a wider range of patient anatomy. Along the same lines, watching Dr. Dobberfuhl do the procedure got us thinking about other design elements we could incorporate to improve usability.

5. What advice do you have for other students who want to become health technology innovators?

Chyna: Make sure your team has shared goals and great communication. I think one of the things that made our project really fruitful was that we all came in with the same desire to take our project as far as it would go. And consistent communication – even on Zoom – was essential to keep us all pulling together, help us work out who was doing what, and decide how much time we wanted to commit to each undertaking. We had regular meetings, either once or twice each week depending on the phase of the project, and a group chat that helped us keep in touch in between.

Remi: Another takeaway is not to be afraid to let what you’ve learned about the need lead your project down a path that’s different from the one you’re used to. For example, most of the people on our team had wet lab experience, but our project ended up needing a device-centered solution. Even though we didn’t have a lot of experience with devices, we were able to develop a functional technology. If we hadn’t been willing to shift, we might not have had such good results.

Original team members: Remi Akindele, Peyton Freeman, Chyna Mays

Course: Senior Bioengineering Capstone

Biodesign NEXT Funding: awarded for spring quarter 2021