Technologies

Novonate Protecting Vulnerable Newborns:

An Interview with Eric Chehab of Novonate

What is the need Novonate seeks to address?

Our project started in the Stanford Biodesign Innovation course, which brings together graduate students in engineering, medicine, and business to address real world healthcare problems. We were originally charged with investigating bloodstream infections linked to the use of central venous catheters. Through our research, we learned that pediatric patients can be five times more likely than adult patients to get these types of infections. And umbilical cord catheters, used to provide nutrients and medication to low birth-weight newborns, were associated with some the highest rates of infection in the hospital.

As our research advanced, we honed in on the mechanism used to hold these umbilical catheters in place. Unlike the prepackaged sterile devices that were designed to protect and support central lines in adults, the nurses use bandages and tape to secure them on neonates. At Stanford they make a little bridge out of non-sterile tape that holds the catheter upright in the umbilical cord stump – it’s like an arts and crafts project.

"Umbilical cord catheters ... were associated with some the highest rates of infection in the hospital."

Ultimately, we decided to focus on designing a device that would more effectively secure and protect umbilical cord catheters in vulnerable neonatal patients in critical care environments.

What key insight was most important to guiding the design of your solution?

Initially, we were focused on infection rates and how to reduce them. But, over time, we learned that the securement of the umbilical catheter was a big concern in its own right. When not sufficiently anchored, the catheter can migrate within the baby’s body, which we eventually realized is a huge concern in its own right and happens in one-third to one-half of all cases. It can also lead to serious complications such as cardiac tamponade [compression of the heart caused by fluid accumulating in the sac that surrounds it] and necrotizing enterocolitis [bacterial infection that severely damages the inner lining of the intestines].

How does your solution work?

Umbilical catheters need to be secured at least as well as adult central venous catheters, but there’s currently no reliable way to do so. These catheters are inserted perpendicular to the body and go through a piece of tissue – the stump – that that needs to dry out over time. So you simply can't use existing central line protection devices that are currently available for adults.

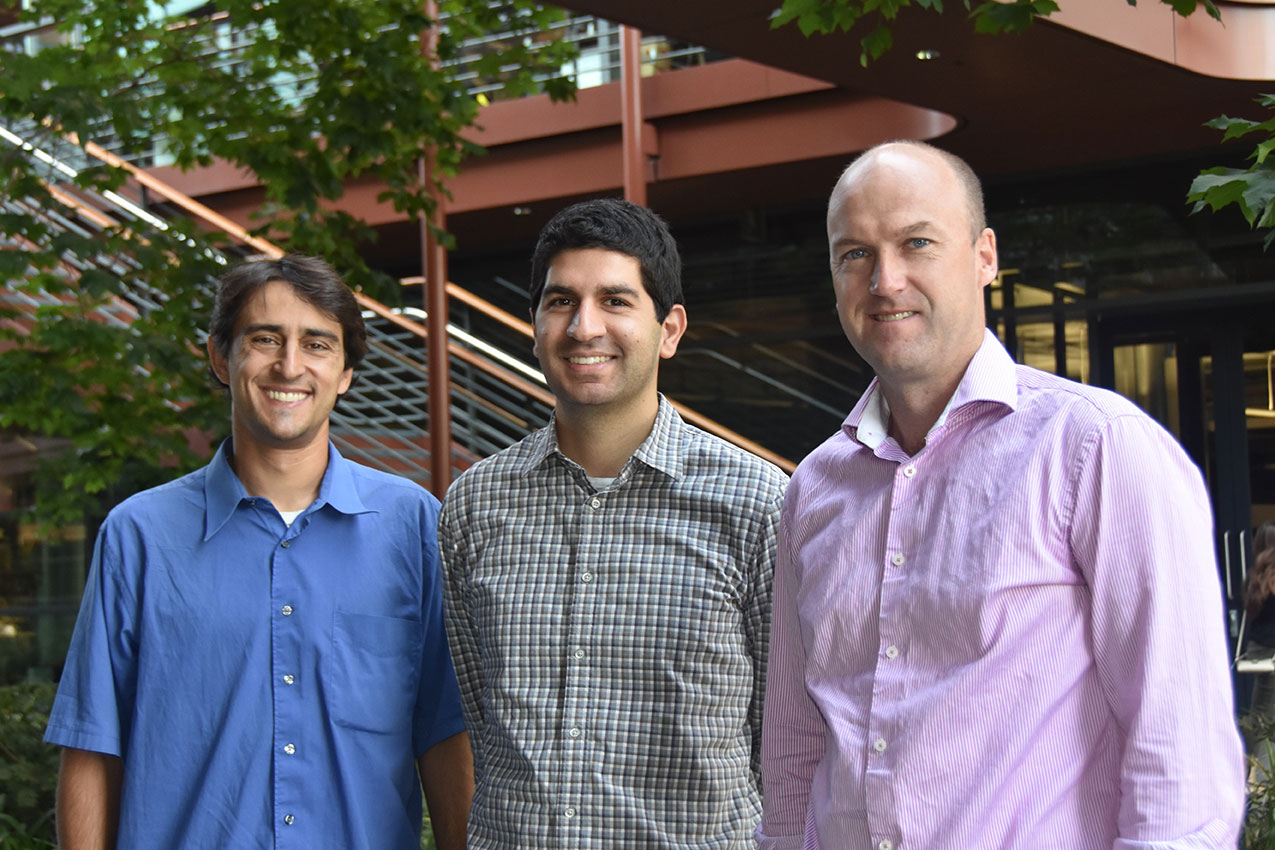

Members of the Novonate team Ross Venook, Eric Chehab, Eric Kramer, and Brian Heckman.

Members of the Novonate team Ross Venook, Eric Chehab, Eric Kramer, and Brian Heckman.

Our device, which we call LifeBubble, is a dome-like structure that’s placed around the umbilical stump to secure the catheters while allowing them to maintain a safer angle relative to the body. LifeBubble standardizes and simplifies the method of catheter stabilization and provides a stronger anchor than bandages and tape.

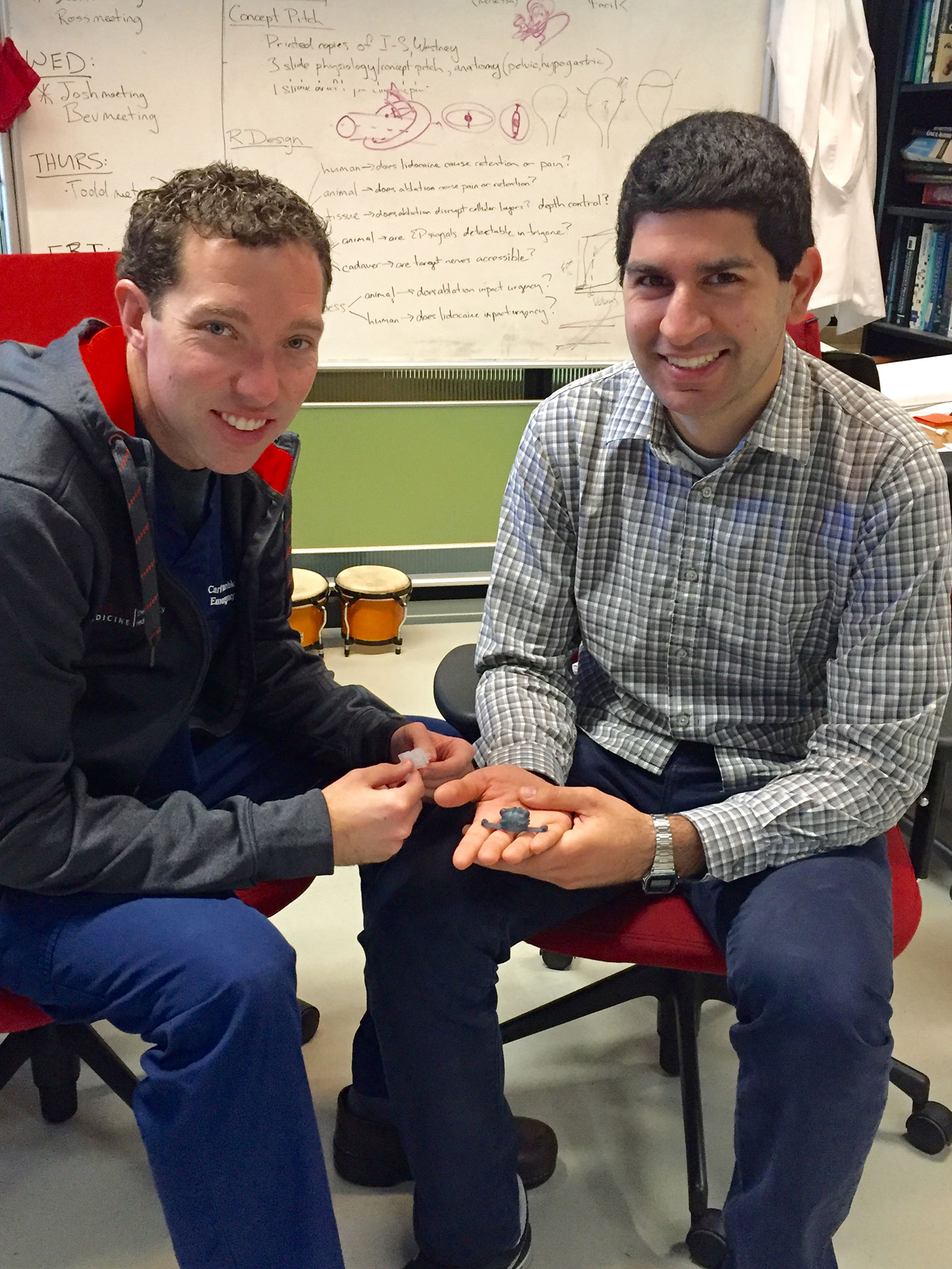

The Novonate solution went through dozens of iterations as the team worked to optimize the design.

The Novonate solution went through dozens of iterations as the team worked to optimize the design.

The dome also protects the insertion site from being touched by care providers, which can be a source of infection. It also has vents that allow airflow to support the natural desiccation of the umbilical stump. LifeBubble does not disrupt the current workflow of catheter insertion and securement. Additionally, it allows nurses to easily visualize the catheter, and they can easily remove or reposition a single catheter which is not possible with tape.

At what stage of development is the solution?

We're currently in the process of manufacturing the device, finalizing our packaging and sterilization methods, and registering the device with the FDA. Our quality system is up and running. After we finish our verification and validation tests, we’ll have a commercially available product that we’ll be able to test clinically.

Tell us about a major obstacle you encountered and how you overcame it.

A couple of obstacles stand out. First, when the Biodesign Innovation course ended, most of the original team moved on to focus on other academic priorities or careers in industry. We had to rebuild the team to keep the project alive, which we did with extensive support from Biodesign Innovation Fellowship alumni James Wall and Ross Venook. As time went on, we also engaged the support of other alumni, including Eric Kramer and Janene Fuerch, as well as a number of student researchers and external advisors.

"Biodesign completely shapes how you think about problems in medicine and how you go about trying to solve them."

Our second challenge was figuring out a viable funding strategy. Only up to 200,000 newborns require an umbilical cord catheter in the US each year, so the market for the device was too small to attract traditional venture capital support. But we were so passionate about the need that we decided to keep pushing forward as much as we could. Our plan was to operate on an incredibly lean budget and leverage as many of the resources available to us at Stanford as possible, including lab space, equipment, and student researchers. We also applied for a ton of grants and sought to join a number of entrepreneurial support networks. Using this strategy, we were able to advance product development and de-risk the technology sufficiently to form Novonate and secure about $300k in grants and $1.1 million in seed funding in less than one year. It was a little bit scrappy, but it worked!

How did your Biodesign training help you advance the project?

Biodesign completely shapes how you think about problems in medicine and how you go about trying to solve them. It taught me the value of fully understanding and characterizing a need before trying to solve it. This doesn’t just apply to developing new technologies, but also to activities such as coming up with an execution plan to move the company forward. As a first-time entrepreneur, I often find myself trying to do things that I’ve never done before or that I haven’t yet learned to do. In each of these situations, I make sure to fully understand the problem, hurdles, and goals before choosing a path so that I can be convinced we’re on the right track.

Eric Chehab founded Novonate out of the Biodesign Innovation course. To learn more, visit the Novonate website.

Disclaimer of Endorsement: All references to specific products, companies, or services, including links to external sites, are for educational purposes only and do not constitute or imply an endorsement by the Byers Center for Biodesign or Stanford University.