Technologies

Acumen Medical Improving the delivery of cardiac resynchronization therapy –

a conversation with Nick Mourlas of Acumen Medical

As Biodesign Innovation Fellows, what is the need you set out to address?

Patients with congestive heart failure who don’t respond to drug therapy may benefit from biventricular pacing, also known as cardiac resynchronization therapy, or CRT. In this procedure, electrical leads are implanted to pace both sides of the heart so that the left and right ventricles contract at the same time. This improved synchronicity can significantly increase ejection fraction [a measurement of how much blood in the left ventricle is pumped out with each heartbeat], which can in turn can instantaneously improve a patient’s quality of life and decrease mortality. It’s a very powerful pacing technology.

The challenge that Christian Eversull, another Innovation Fellow in my class, and I set out to address was around the delivery of the left ventricle lead. ‘Brady pacing,’ where the leads are placed into the right atrium and/or right ventricle, had been a standard procedure for many years. But pacing the left side of the heart is much harder because the electrical lead has to be placed and anchored in the coronary sinus vein.

“This improved synchronicity...can instantaneously improve a patient’s quality of life and decrease mortality.”

Delivering and then fixing this lead so that it doesn’t dislodge is a technically challenging procedure that is affected by the unique anatomy of each person’s coronary sinus and its tributaries. As a result, despite the effectiveness of CRT, physicians were failing to deliver the lead in 25-40% of patients, at the time. And so patients with severe congestive heart failure, which has 50% mortality within five years of being diagnosed, would go in for this procedure, but come out and have the doctor say, ‘We’re so sorry, you have some unusual anatomy and we can’t help you.’

We thought there was an opportunity here to develop something to make it easier to place the lead in order to help patients who were not currently being served.

Nick Mourlas, Steve Leeflang, and Chris Eversull, co-founders of Acumen Medical

Nick Mourlas, Steve Leeflang, and Chris Eversull, co-founders of Acumen Medical

What key insight was most important in guiding the design of your solution?

For a number of reasons, in most CRT procedures physicians are only able to use fluoroscopy to try to locate the coronary sinus, which means they end up poking along the back wall of the heart to try and find it.

We thought that if they could see where they were going, it would be much better. So the genesis of our thinking was to provide easier access to the coronary sinus.

Then, another challenge once they’re in the coronary arteries, was navigating into the branches and getting through torturous vessels. So we thought another improvement would be to create a tool that wasn't a rigid catheter. We envisioned something that had a low profile and was maneuverable, and then opened up to allow the lead to pass through. That was the second innovation.

Our mission was to revolutionize the delivery of therapeutic devices and left ventricular pacing leads for cardiac resynchronization therapy by changing the method of visualizing and navigating the heart’s anatomy.

How does your solution work?

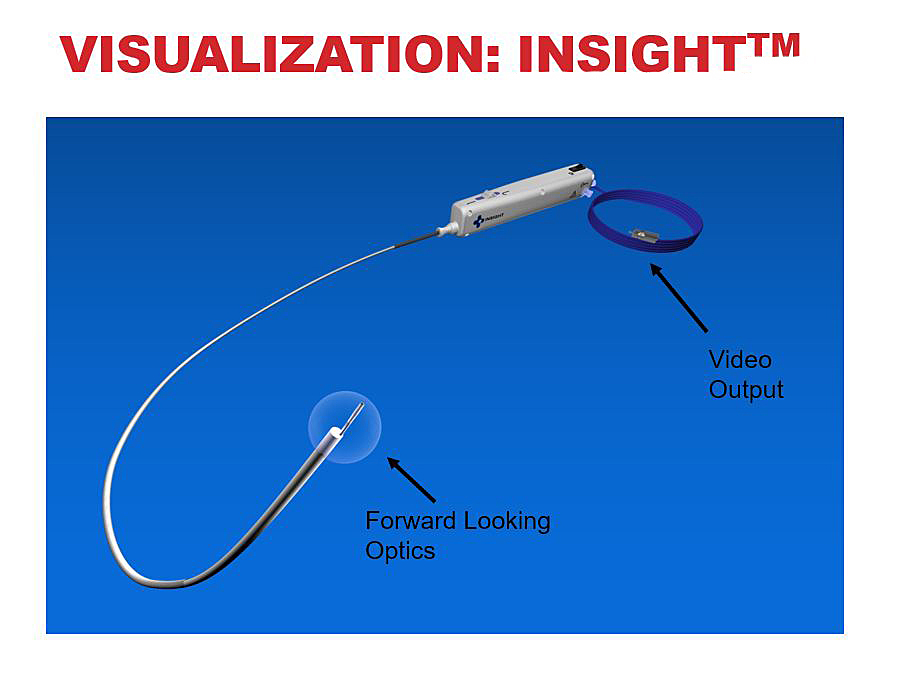

Our first technology was a steerable cardiac endoscope, which is a visualization tool. This device can navigate anywhere in the right atrium and it supplies full color images to help find and cannulate the coronary sinus. The device was compatible with any monitor that had a standard RCA input, and it was completely disposable. So it was a visualization platform that required no capital equipment.

This short promotional video, provided by Acumen Medical, illustrates how the Insight endoscope is intended to work (see endorsement disclaimer below).

This short promotional video, provided by Acumen Medical, illustrates how the Insight endoscope is intended to work (see endorsement disclaimer below).

Our second tool was a flexible conduit in a lubricious sheath to help navigation once the physician is inside the coronary veins. This addressed navigation and fixation with localized visualization via targeted contrast injection and fluoroscopy, and augmented pushability which allowed delivery through tortuous anatomy and facilitated better axial force transfer to the distal tip which helped reduce lead dislodgement rates.

At what stage of development is the solution?

By the end of the fellowship we had cobbled together some works-like prototypes that convinced us we could make the technology work. So we decided to keep pressing forward. We added an additional team member, Steve Leeflang, who, like Chris, had an engineering background, and the three of us founded Acumen Medical together.

“One of the best parts of our fundraising story...was that the clinicians we worked with originally to validate our concepts were our first investors.”

The most important validation for us – one of the best parts of our fundraising story throughout the life of the company– was that the clinicians we worked with originally to validate our concepts were our first investors. We licensed the technology from Stanford OTL and with their help, bootstrapped enough funding to get from a slide deck in January 2003 to first-in-human at the end of the year. Over the next five years, we raised more funding, and aggressively worked on product development, regulatory approval, and early-stage commercialization of the technology. We also added another device, a delivery system for a Medtronic pacing lead used in the right side of the heart that allowed the operator to deliver it with a smaller diameter catheter. This captured Medtronic’s attention and they acquired Acumen Medical in December of 2007.

Tell us about a major obstacle and how you overcame it.

In the early days of our commercialization effort, I was flying across the country to introduce physicians to our approach and hope that a trial case or two would convince them to adopt the technology. I was having great success getting them interested and training them to use the devices, but there’s only so much one person can do. So, at some point we decided to build a sales force. We hired our first class of sales representatives, but were surprised to see that they had less success. I think that the entrepreneur going out and representing his or her technology has a certain uniqueness that piques the doctor’s curiosity and makes them more likely to want to spend the time to learn more. But they see sales reps all the time, and their level of interest just isn’t the same. So while a company gets more bandwidth by working with reps, there’s just a lot of positive aspects to the entrepreneur going out and forming those first relationships. There’s no great solution to this, but it’s definitely something for innovators to keep in mind as part of their strategic planning process.

Reflecting on your experience, what advice to you have for other innovators?

The Biodesign Innovation Fellowship is one of the best ways to get into the medical device industry. I would not have been the founder of a medical device company right out of graduate school without the fellowship. The combination of clinical exposure, experience, and the Biodesign industry network put me in a position to be able to do that, as well as connecting me with my partner, Chris. At Acumen, I was very fortunate to be able to take something from concept all the way through early commercialization, and that experience opened the door to everything that followed, including my current position as Senior Director for New Ventures at Johnson & Johnson Innovation.

Nicholas Mourlas and Christian Eversull founded Acumen Medical out of the Biodesign Innovation Fellowship in 2002.

Disclaimer of Endorsement: All references to specific products, companies, or services, including links to external sites, are for educational purposes only and do not constitute or imply an endorsement by the Byers Center for Biodesign or Stanford University.